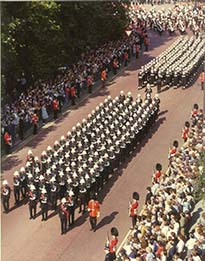

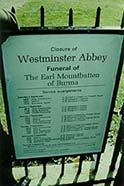

Ceremonial Funeral of Lord Louis Moutbatten of Burma

Written by Godfrey Dykes

© RN Communications Branch Museum/Library

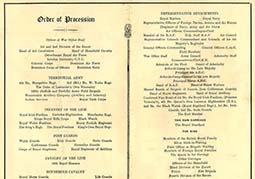

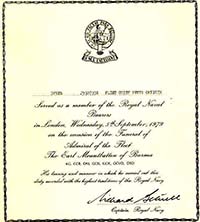

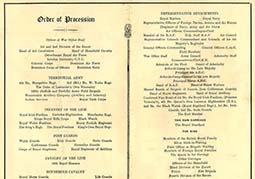

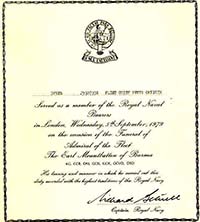

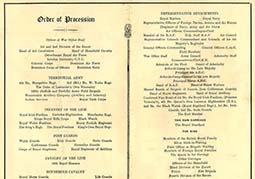

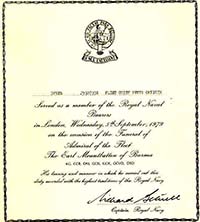

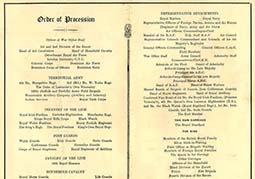

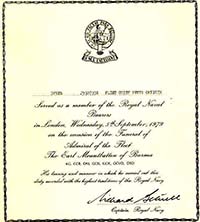

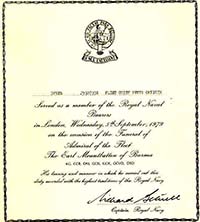

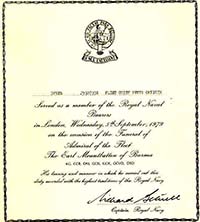

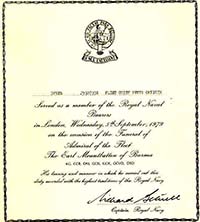

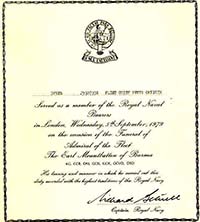

The outline planning, obviously done before the death has enough detail to make it easily convertible into an operations order the moment the person is known to have died. In Lord Mountbatten's case, it was suggested that he had almost written the whole of the outline planning document, which in itself was very detailed involving no fewer than 507 personnel from the Royal Navy and Royal Marines. In his official biography, an excellent book written by Philip Ziegler and published by Book Club Associates by arrangement with William Collins Sons and Co Ltd, Philip Ziegler describes Lord Mountbatten's approach to the task of planning his own funeral. By the time the General Officer Commanding London District had written his actual funeral operations order, Mountbatten's numbers had increased three-fold. As an example I have included just the front page of each of the orders (outline and operational) which are, regrettably, difficult to reproduce here. The outline planning document dated 1977 was a revision of the outline planning document dated 1975 and is a Naval document; the funeral proper, is the Army document dated the 31 August 1979, a few days after the Sligo murders.

Each document has many more pages with planning down to the very last detail. Here, I must tell you that not all in the OP Order followed the request made by Lord Mountbatten, namely, that the Bearers should be members of the Communications Branch of which, he was the senior member. In the 70's, HMS Mercury (the alma mater for all Communicators) had a First Lieutenant and an appointed Assistant, known as XL (Executive Lieutenant). Officers appointed to this job were not necessarily Communicators although many were. In 1979, XL was an aviator who had pranged his helicopter whilst flying too close to a destroyer! When he appeared in HMS Excellent as being the second officer (as per op order) from HMS Mercury - Gordon Perry was the other officer and a proper Communicator - the Whale Island 'mafia' seized upon the opportunity to replace him. If HMS Mercury could not supply a Communicator, then the prestigious job was up for grabs, and Lieutenant Robert E Doyle, of HMS Excellent replaced HMS Mercury's XL. After the funeral, Bob Doyle wrote to me saying that he would always consider himself an honourary member of the Communications Branch and no other officer could have performed that job better than he did. Lord Mountbatten would not have been displeased.

On Wednesday morning I arrived in HMS Excellent at 0815. The weather was warm and sunny and my thoughts were with Lord and Lady Brabourne and their son Timothy who were in hospital in Sligo recovering from their wounds received in the cowardly boat bombing; they would miss the funerals of their son Nicholas, Lady Brabourne's father and Lord Brabourne's mother.

It was a hectic day in every sense for all concerned, both instructors and students. We had so many problems that at times some of them seemed insurmountable. Approximately three hundred men of every age, shape, size, frame of mind, who had come mainly from the Portsmouth and Plymouth areas, arrived in dribs and drabs. Just about all of them were in need of a haircut, and because HMS Excellent was in the middle of summer leave, there was no barber available and the men were not particularly displeased with our obvious predicament.

Some years ago it was decided that the traditional sailors suit (the type I had worn from 1953 until 1963) was outdated and should be replaced. The time scale for sailors to change from the old to the new (a more relaxed and informal style of uniform) style suits (considered hideous by many of us older hands) was extended until late 1979 or early 1980. On that Wednesday, half our three hundred sailors had the old suits and the other half the new ones, or, none at all (they had been left at home). To complicate matters further, of these three hundred men, there were many Chief Petty Officers and Petty Officers who had volunteered for the Gun Carriages Crew. They had to be dressed as ordinary ratings in sailor's suits, and therefore they had to swap the peaked-cap (fore and aft rig) for a round-cap (square rig). They were subsequently issued with a full sailors uniform (new style) at no cost to themselves; the suits being written off the by Ministry of Defence.

For Ceremonial to be effective, sizing of men with similar stature is essential but almost impossible with twenty percent of the men to be sized out of HMS Excellent in civilian barber shops being shorn of their over long hair. No sooner had a six foot tall rating been put alongside a five foot eleven inch tall rating and the two paired for a specific position, than a new six foot tall sailor would arrive and the original pair split up, re-paired and re-briefed.

A rather sweet young lady arrived in HMS Excellent at lunch time having been recruited as a temporary ships barber. The sailors soon got wind that she was a 'hair butcher' and the last I saw of that drama was a room full of young Wrens awaiting the scissors, and at least one of them had very wet eyes!

From lunch time onwards things began to gel, and by tea time of a glorious day, sizing was near completion.

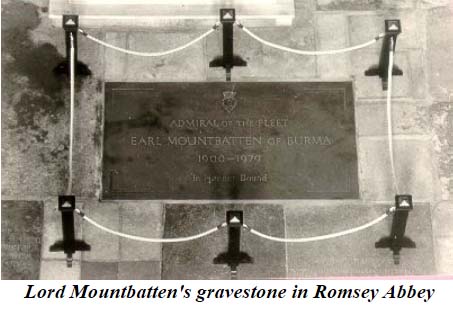

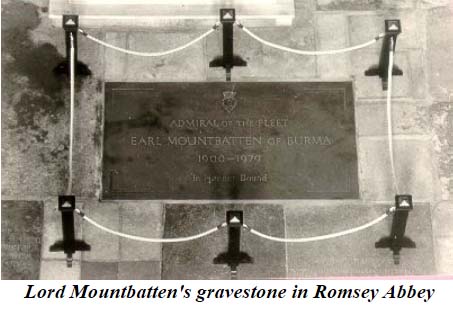

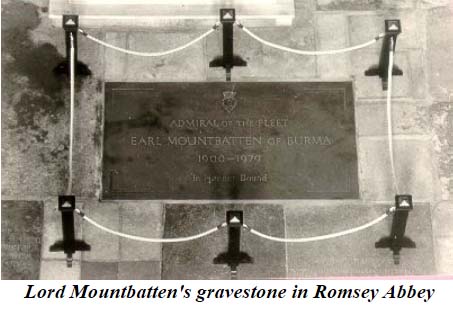

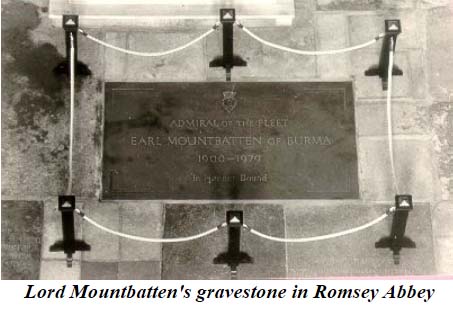

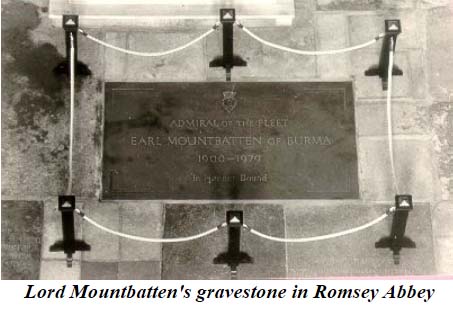

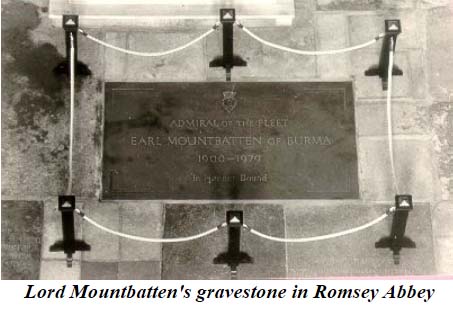

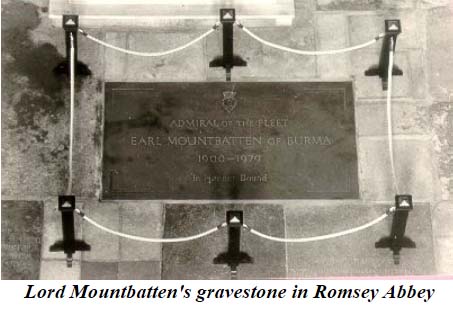

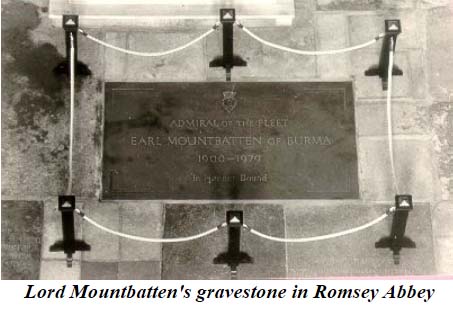

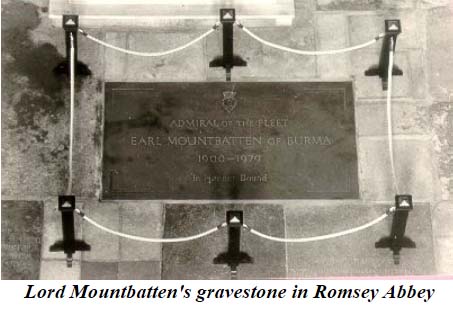

At 1730 I was officially informed that I was to have the lead part in the Ceremonial London funeral and that I had to pick eight very strong and physically similar sailors (with two spares) for the London Bearers, and that FCCY Leslie Murrell MBE, the Romsey Warrant Officer, would pick his team for Romsey Abbey where the private burial would take place. The pride I felt at being told what function I had to execute was immense and immeasurable, and I became rather emotional. I went to the toilet to be alone, to be in reach of something to wipe a tear and to wash away its stain. My thoughts were racing and I was trying to imagine what the actual event would be like and whether or not my recurring stomach illness (I had major abdominal surgery in 1976) and my left knee (which partially seizes after long walks) would let me down and bring irreversible disgrace upon myself. I was 41 and in the twilight years of my naval career. The funeral of a murdered Royal would obviously be an emotional time for the nation and for all those who were to take part in the Ceremony. In the privacy of my surroundings I found it difficult to believe that I had the honour to represent the Royal Navy.

After sizing, sailors were put into Groups and assigned to special tasks e.g., Bearer Parties, Gun Carriages Crew, Marching Escort and Westminster Abbey Lining Party. The Navy also supplied many officers and ratings for Street Lining, but HMS Collingwood undertook the training of this Group, and apart from seeing these men at rehearsals in London and the day of the funeral proper, we never met or worked with them.

Several professional barbers were promised for the next day. Payment was organised to cover the days ahead, and a mobile clothing store would be on hand for new caps, boots, suits etc., at a price.

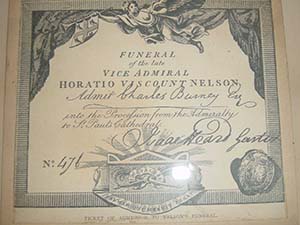

Before I mention the Gun Carriage in this funeral, I want to tell you about how the Royal Navy started its association with it, at State and Ceremonial funerals.

This picture shows Eastney Royal Marines Barracks. In the centre of the picture from foreground to background is the Marines accommodation block. To the left of it and not far from being the same length, is the indoor Drill Shed.

To the right there are two grassed areas with a large Parade Ground in the middle, and to the top and upper middle right, the sea and promenades.

Used as a Hearse, the Gun Carriage is a 20th century precedent, at least for the Royal family. Before that time, the Hearse was a horse drawn vehicle bedecked with heavy funereal artefact, the horses as much as the funeral car, and the followers were usually pedestrian. When a Royal died in residence, that is at Windsor Castle as did George III, George IV, William IV (Victoria's immediate predecessors) and Prince Albert, their funerals were 'in-house' as it were, negating the need for Ceremonies outside the Castle, and certainly not in London.

London had not long ago witnessed the 'funeral of all funerals' (but on a par with that of Lord Nelson in 1806) and certainly one of the longest Processional routes of all time, when in 1852 the nation said its goodbye to the Duke of Wellington, just 9 years before Albert's very private funeral. It was calculated that those wishing to say goodbye to The Duke of Wellington would be so great, that they built a funeral car of enormous height to be pulled by many horses, (16) , on top of which they placed his Coffin in clear view to all from Chelsea Pensioners home to St Paul's Cathedral. Those of you who know London will appreciate this huge distance! That funeral car is preserved and on show at The Duke's ancestral home at Stratfield Saye in Hampshire, another must for history buffs.

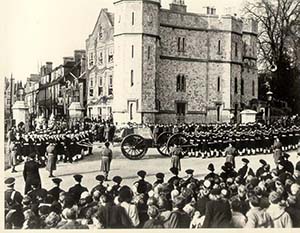

When Queen Victoria died at Osborne House in 1901 she was the first Monarch to die away from Windsor since George II who died at Kensington Palace in 1760. It was she who had the first of the State/Ceremonial funerals we speak of today, where the Monarch's body has a lying- in- state ( usually in Westminster's Great Hall with plaques in the floor to show where each and every Monarch has laid -in- state in years gone by, (another big must for Royalists)) so that their subjects could pay homage and say goodbye, followed by a Ceremonial Procession through the streets of London to Paddington Railway Station and from there by Royal Train to Windsor. At Windsor, the Ceremony would continue with a second Procession from the Railway Station leading to the steep steps outside the West Door of St George's Chapel in the Castle. There, the Church Service would take place and the Monarch's Coffin would be lowered into the central vault. At a later time and in private, the Monarch's Coffin would be moved to its appointed place usually within the Chapel (though Albert and then Victoria were moved out of the church and the Castle to the Mausoleum at Frogmore within the grounds of Windsor Castle) to rest in peace. There are 11 Monarchs at rest in the Chapel.

At Queen Victoria's death, her body was moved from Osborne to Cowes on the Isle of Wight and thence to the mainland, with great dignity

Queen Victoria did not have a London, funeral (nor a lying-in-state) but merely passed through a small section of it (a route measuring approximately 4.2 miles) whilst transferring from her arrival station to her station of departure to Windsor viz, Waterloo to Paddington. This picture from Olivia Bland's The Royal Way of Death, gives one the overall feeling of State Pageantry with the footmen and horses almost dressed for a happier event like a Coronation.

In fact, by her own hand and written funeral arrangements, it was just that, a happier event, and you will note that the Queens coffin is draped in brilliant white, overlaid with her personal royal standard, and none of the trappings is funereal suggesting gaiety. In her coffin the Queen was dressed in her white wedding dress and veil. Gone the morbidity of her own grieving for the loss of her own husband, and in came a return to normality, a normality normally seen after a decent period of bereavement. The train station that serves Windsor Castle is called Windsor and Eton Central, immediately under the great clock of Windsor Castle, and that station is fed from Paddington. However she arrived in London at Waterloo having being diverted from the Gosport line to the Portsmouth line - see the train route on this page Portsea OS Map 1898. The coffin therefore had to be transferred from Waterloo to Paddington and this, as the picture shows, was done using a splendid bedecked gun carriage pulled by horses from the Royal stables guided by members of the Royal household. Part of the route passed by her home of Buckingham Palace as painted in the picture.

However, the Windsor Ceremonial funeral was a shambles as the following text and picture show.

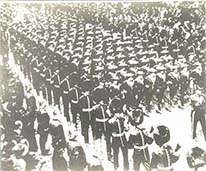

Note how the sailors are looking everywhere instead of to their fronts. It must have been extremely embarrassing for all who observed this undignified scene. The text comes from another excellent book which I recommend called Whaley - The story of HMS Excellent.

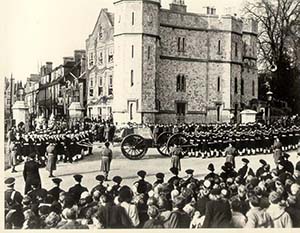

With Queen Victoria the precedent was set, namely that from henceforward, the Monarch (irrespective where he or she died) would have a State funeral with Ceremonial in London and in Windsor, and this has continued with the deaths of Edward VII, George V and George VI.

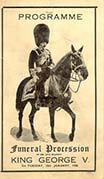

Queen Victoria's London Ceremony, as you have seen, had, as a centre piece, a Gun Carriage pulled by horses from the Royal Household whereas Edward the VII's London Ceremony was centred around a Gun Carriage pulled by the Royal Horse Artillery. The Royal Navy's involvement with the Gun Carriage for both London and Windsor State Ceremonial started with the funeral of George V.

§In truth there are one or two accounts of this episode and what follows is given by the most important man in the land when it came/comes to State Pageantry namely the Earl Marshall of England the Duke of Norfolk.

King Edward VII Funeral Arrangements

And this one which is an account taken from the funeral of King Edward VII nine years after Queen Victoria's death in which he suggests that the horses were spooked by an eerie silence as well as by the cold: Bluejackets

However, I am extending my red double 'S' sign § to an article further down this page, so I am going to ask you to keep an eye open for the double 'S' mark § which is quite some way below but very obvious, and coincides with an article in brown-coloured font. This new article is without doubt the correct version of what really happened and is written by one of the officers most involved with the gun carriage.

Since you have now read the reason for the Royal Navy having the privilege of pulling the Monarch's Coffin on a Gun Carriage it becomes obvious that there must be a Gun Carriage in London and a separate Gun Carriage in Windsor. Two quite separate Crews would be required each with different skills and training. It fell to Chatham, the Naval Base in Kent (and closer to London than Portsmouth) to supply and man the London Ceremonial Gun and for Portsmouth, the Naval Base in Hampshire, the Windsor Gun.

The Portsmouth Gun

The Chatham Gun was kept and maintained at Woolwich and the Portsmouth Gun in HMS Excellent. The basic difference in training was that London is more or less flat with exceptions like Ludgate Hill in the City (for St Paul's), but Windsor has steep hills which could be darn right dangerous.

Here are two pictures of King George VI's funeral at Windsor, the one on the left explicitly showing the hilly terrain, but the one on the right hides the fact that the front drag-ropes are about to go into first gear at the foot of the hill ahead of them.

The Gun had to be taken from the Windsor Railway Station to the step's at the West Door of St George's Chapel within the Castle, which as the crow flies is a short distance (I would guess somewhere near 200 meters). However, because that 200 or so meters was up and down hills (and very steep hills at that) the Gun travelled in a zig zag fashion along parallel streets until the approach to the main private vehicular entrance (now also the main entrance to the Castle for pedestrian visitors) was less of a challenge. The uphill task led to the Castle's Upper Ward (the Royal apartment's are in the Upper Ward), past the statue of Charles II, down through the Norman Gate into the Middle Ward, and then downhill into the Lower Ward ultimately to the main entrance of St Georges Chapel. This challenge involved great strength (uphill by the men in front pulling, and downhill by the men behind acting as a brake) whilst all the time keeping their timing, their bearing and their dignity, trained not to show the physical strain they were under and conscious that they were the 'engine' of the Royal carriage bearing the coffin of our much loved and deceased Monarch. Believe you me, a great honour for those sailors.

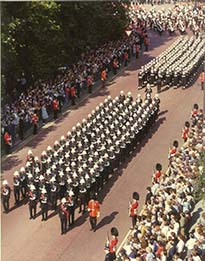

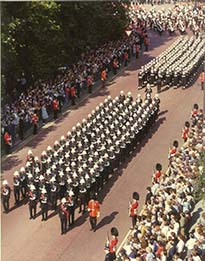

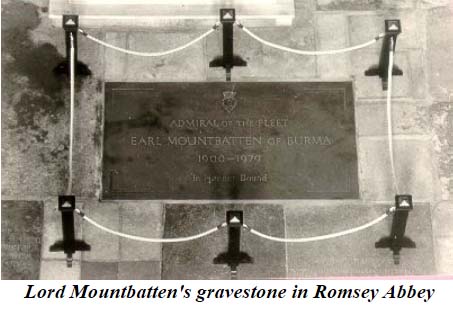

These next pictures are of the funerals of Edward VII, George V, George VI, Winston Churchill and Lord Mountbatten. Clearly, the Navy had mastered the necessary technique at these funerals! The other pictures show the Royal Navy ranks the Royal Family held in in the late 70's early 80's. The events between death and burial of a Monarch are sometimes confused, and the word Funeral is taken to mean an event. In reality, there are several events (at least more than one) as the following example shows. When King George VI died in 1952 at Sandringham, his coffin, pre-made of Sandringham oak just like that for his father King George V) was taken from Sandringham House to the tiny estate church of St Mary Magdalene, a typical village church, small, dignified, peaceful, in which the King worshipped every Sunday during his residence at the house and where Estate workers stood their vigil for three full days of total and utter privacy. Then, on the fourth day (the sixth day after death), the coffin was taken on a horse-drawn Gun Carriage (RHA): (this gun carriage was the gun carriage used at the funeral of HM Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother in London) to the local Railway Station of Wolferton and brought to London by train to Kings Cross, where from, and only ten days before, he had left London for his beloved Sandringham: that was phase one and two. At London's Kings Cross station, his coffin was met with all the trappings of State and was taken in a Ceremonial Procession by a RHA-drawn Gun Carriage supplied by Woolwich , to his Lying-in-State Ceremony at Westminster Hall some three miles away with countless thousands looking on : phase three. The next phases involved the Royal Navy and its two Gun Carriage's to the full, phase four being from Westminster Hall to Paddington Railway Station (a one mile journey via Whitehall, St James's Street, Edgware Road, Sussex Gardens etc.,) where the King left his sorrowing and mourning London, to phase five , from Paddington to Windsor and Eton Railway Station, and thence, phase six from the station to St Georges Chapel in Windsor Castle, all phases constituent parts of the Funeral. The steam locomotive which pulled the Kings coffin from Paddington was called the Windsor Castle and had a Royal Crown on top of its engine just forward of the engine funnel. It is important to understand this, because subsequently, any one of the four Gun Carriage's used for King George VI, could be used as the Gun Carriage for a Ceremonial Funeral as was the case for Lord Mountbatten, and more recently, HM Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. Whilst I am not qualified to comment upon army ceremonial at Royals funerals, it is my understanding that the guards also alternated (as did our naval gun carriages) for King George VI funeral, where, at Kings Cross station, the coffin was borne by Coldstream Guards en route to Westminster Hall, but for the State Funeral proper, by members of the Kings Troop Grenadier Guards.

The Portsmouth Gun and therefore, the Windsor Gun.

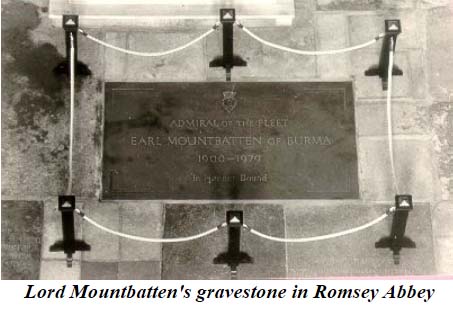

The Gun Carriage, which had been used for King Edward VII, King George V, King George VI and Sir Winston Churchill, was brought out of its show case and made ready for another Ceremonial funeral. It was a massive and beautiful object weighing nearly three tons. It had been given to the Royal Navy for safe keeping by King George V after the funeral of his father King Edward VII, and it had (has) pride of place in the centre of HMS Excellent covered by a glass case.

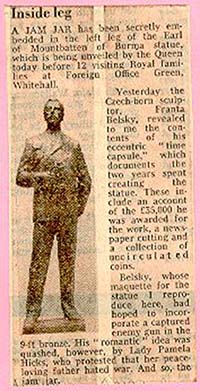

It was not until Friday morning when Mr Michael Kenyon, the Royal undertaker, sent the measurements of the Coffin that we realised the Gun Carriage Coffin platform was about two inches too short at six foot six inches. The Shipwright Officer and his staff had to add a two inch block to the head-end, and thereafter, to re-site the Coffin locking bar which was to hold the Coffin in position during its journey from St James's Palace to Westminster Abbey. They did a good job, and the colour matching and texture of paint to match the Guns deep green, was perfect. We saw little of this Gun in our Portsmouth practice days and we used a Royal Artillery Gun in lieu which had been used in London for the State funeral of King Edward VII.

The second day ended at 2030 and I travelled home with men who had been brought in from the aircraft carrier HMS Bulwark. We talked of nothing else but the forthcoming event and of how proud we were to be involved. I got indoors at 9pm very tired, but from now on, very high on the event to come. I hardly slept a wink!

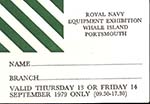

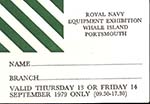

On the 30th August we began training for real at the Royal Marines Barracks at Eastney, Southsea. I had gone there by car, but the bulk of our manpower was transported daily to and fro between HMS Excellent and Eastney by lots of RN thirty-six seater coaches. Eastney was used because the traditional training area, the Parade Ground at HMS Excellent was being used to stage the Royal Naval Equipment Exhibition (RNEE) Click to enlarge, and because of leave, there were no Royal Marines in the Barracks, so we had the place to ourselves.

RMB Eastney then*** was ideal for our purposes and the glorious early autumn weather allowed us to use the large Parade Ground and the equally large indoor Drill Shed to best advantage. The Royal Marines museum was open for business as usual, and so from the word go those Groups training on the Parade Ground were open to inspection by the public visiting the museum as well as by holiday makers viewing from the Barracks perimeter railing which ran along the sea front parallel to the promenade. The public therefore witnessed our early training and all the errors of drill we made. They must have viewed the event with horror and feared for the great British Pageantry.

*** Eastney today, is now a partition where the officers mess/wardroom is the Royal Marines Museum; the barracks proper is now called Marine Gate Estate, a mixture of various types of properties. However defined, a sad place today compared with the Home of Royal Marines proper many of whom took part in this, the last of the massive and splendid Royal Funerals. It is doubly upsetting, that this area is now the venue for wedding receptions and other parties where the Museum Authorities themselves sell alcohol resulting in the encouragement of loutish behaviour bringing the dignity of the Museum to an unacceptable level.

From about 0930 until lunch we practiced the 'Bearers slow march' which was painfully slow and laboured, by slow marching up and down the Parade Ground. The normal Naval way of marching (or walking for that matter) is to step off with the left foot swinging the right arm forward, although one often sees the left arm working with the left leg when people are trying a little too hard to remember what comes naturally! If a member of a Group, the only real worry is to remember to keep in step and to move in unison. Marching with a Coffin, where each man steps off with his inside foot i.e., left hand four men with their right foot and the others with their left foot keeping step with the person marching in front of the Coffin, is not so easy. This method of marching was alien to Naval Ceremony which dictates that the first bang on the drum on stepping off should coincide with the left foot. The reason for marching in this peculiar fashion is to stop the Coffin from swaying side to side, and synchrony of step had to be achieved before we started to use the practice Coffin. By the time we broke off for lunch we were coping well as a team, and I sensed a growing esprit de corps and pride of purpose amongst my charges young and not so young!

Early on in the proceedings Bob Doyle and I had watched a small portion of the State Funeral for Sir Winston Churchill (January 1965) taken in St Paul's Cathedral enroute from the Great West Door to the catafalque placed under the dome. Frankly it was a shambles although it is not my intention to apportion blame! The shambolic march could have been caused by several reasons but whatever it was, the coffin travelled in a crab like fashion up to fifteen degrees off its centre line of approach with the right hand bearers nearly off the carpet, often nearly colliding with members of the congregation sat on the right hand side. However, one possibility was that the bearers feet and thus their body movements, were out of synchrony, and it proved to be an embarrassing sight to the trained eye. Below is a snippet. Note the straight line of approach of the warrant officer leading the bearers with areas to his left and right of equal distance which also applied to the officer at the rear (head end) of the coffin. The coffin itself should have been behind this warrant officer but as it was, the left hand bearers ended up in that position. Although a tall order because soldiers, especially foot guards, are well trained in ceremony whereas we were not, we nevertheless vowed that at all cost, we would get this part right and we did.

What you are about to see I took from YOUTUBE quite early on which was the original filmed footage and ALL in black and white - no colouring of any sort. WE ARE EXTREMELY LUCKY in being able to show you the original and full story of that walk. The only other State funeral [which the navy rescued] was that of Queen Victoria’s in 1901, another potential disaster !

In 2015 this is what YOUTUBE announced for the new version of the State Funeral 50 years after the historic black and white original was made.

THE STATE FUNERAL OF SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL (NEWS IN COLOUR)

COLOUR IS VERY GOOD

YouTube - 460,000+ views - 21/07/2015 - by British Movietone

It is my belief that the foot guards performing the role of coffin bearers were so appalled that the public should see what you will view in the link below - Crab Like Fashion - that they asked YOUTUBE to alter their film which they obviously agreed to. They changed the film from black and white to a coloured version, by disregarding the original and adopting a British Movietone version, but colour or black and white, they couldn’t rid it of the enhanced swaying of the coffin which was so noticeable to those seated in the pews to the right (the South Aisle) as one approached the dome of the cathedral, that many prepared themselves to move to their right to make sure they would be out of harms way should the coffin collide with the congregation at any point.

However much they might have tried they couldn’t succeed so they took away a whole section of history and actually deleted the major part of the long walk from the great west door to the catafalque leaving us seeing only the entrance of the coffin and the latter part of the walk as they approached the seated positions of Her Majesty The Queen and The Duke of Edinburgh sitting to the right of the catafalque; in effect a large section of the 475 foot section!

To give you some idea of the crabbing effect of the coffins transit through the great nave of the cathedral open the link below of - Crab Like Fashion -, put your mouse pointer on the circle at the leading edge of the progress bar and pull it as quickly as you like and as many times you like, to see in a dramatic fashion the movement of the coffin as it passes through the nave, which from entrance to catafalque is approximately 475 feet in length.

It is generally thought by those in the know, that the guards with that long and precipitous climb from street level to the great west door were unnerved by an incident which took place when a steady pace had been maintained by the guards with an exceptionally heavy coffin weighing approximately a tad short of ½ a ton.

Eight pall bearers from the finest and most famous men in the land were chosen (including Mountbatten). Normally the pall bearers march/walk alongside the coffin but on this occasion they proceeded throughout ahead of the coffin. Churchill’s Partner in dealing with the winning of WW2 was now in 1965 a frail old man but he insisted, rightly, that he should be a pall bearers to his dear old friend to say his goodbye. There were many people, some as individuals others as groups, simultaneously climbing those steep steps to gain access to the cathedral, some ahead of the coffin and others behind or to the side. As the weight of the coffin was beginning to show in the faces of the guards, Lord Atlee ahead in the pall bearers group tripped and had to be supported by an admiral and a general, also pall bearers, his frailty telling, but he insisted he wanted to continue. The guards were close behind and they had to slow their pace, even dwelling a pause momentarily but it was enough to affect their locomotion and rhythm, translating to an increase of weight in the coffin. The coffin was very nearly dropped both going up and coming down. More guardsmen than planned came to assist by acting as pushers but equally stoppers if the coffin were to slide backwards. No doubt their legs started to turn to jelly, and despite many rehearsals this unforeseen stumble had unnerved them for the march to the catafalque, although fortunately by the time they had reached the front pews of the nave they had regained their momentum and were back on track and fit for purpose exactly as we would expect of this fine body of men, and The Queen had not been aware of this temporary hiatus. More nerve racking times were ahead on leaving the cathedral when some of the bearers really struggled to hold on to the coffin now pointing downwards at a steep angle. That their mettle befitted an infantry man was obvious, and they did themselves proud as well as the armed forces and the country.

Crab like fashion

Lunch, on all our days in Eastney was a cold salad buffet brought ready to serve from HMS Excellent. It was adequate for the men with soup and fresh fruit or fruit yogurt, but a monotonous diet. Like so many others, I had too much on my mind to be really interested in food. Whatever, the catering staff had a difficult job to feed three hundred odd men on a self service basis in less than one hour, and they did it well without complaints.

During my lunch break I talked with many civilians, holiday makers who had entered RMB Eastney ostensibly to see the museum but the sound of the Royal Marines Mass Bands had been too much of an attraction for them. They were elderly couples in the main, full of sympathy, who were keen to know what was going on. During that first day of training, I had a sneaking suspicion that the ladies were dying to mother young sailors, and the men were dying to smother others for their incompetence and mistakes. I should record here for posterity, that none of our men was Ceremonially trained (like many soldiers are) but ordinary sailors - cooks, stewards, engine room men, computer men, clerks etc - who had volunteered or who had been detailed. The Instructors too, although excellent men and proficient in their trade, were not immediately conversant with the special drill procedures. The last time the Royal Navy had trod the streets of London pulling a Gun Carriage was fourteen years ago at the State funeral of Sir Winston Churchill, and the expertise gained during that time had long since been lost to the Service. I wonder whether these same elderly couples who watched the funeral Ceremony changed their minds about our Military Bearing?

Additionally, each Coffin had its own weights and trestles. One was made of ordinary pine and the other was painted grey. We, the London Group took one Coffin plus accessories to one end of the Drill Shed and the Romsey Group theirs to the other end. From this time on, both Groups practiced in the privacy of the Drill Shed away from the Parade Ground, the civilian on-lookers and the inevitable ghouls. From the beginning, the very obvious requirement of knowing how heavy the actual Coffin would be was to be kept from us despite many enquiries. The time we did get to know we were lifting it on the evening before the funeral day at St James's Palace! We were regularly told that the Grenadier Guardsmen who carried Sir Winston Churchill, carried one thousand pounds, and many speculated that Lord Louis's Coffin would be similarly constructed of solid oak and lined with lead. We were given four large sand bags and told authoritatively (in a manner of speaking) that the Coffin plus the sand would give us a realistic training weight. It was comforting to know that Leslie Murrell and his Romsey Bearers were doing exactly the same thing. Training started with an empty Coffin so that we could get the orders and corresponding movements worked out before putting the muscles to work. The movements were basic and soon mastered. They involved the Bearers slow marching, with our special step, towards the Coffin, halting when the two sailors who carry the feet-end arrived at the head of the Coffin, turning inwards to face one another, raising their hands to chest height palms uppermost, both feet-men pulling the Coffin off its rest platform using the head handles, and the Bearers passing the Coffin down amongst them by hand movements. When all their hands were in place, the order was given to lift. At this order the Bearers raised the Coffin to shoulder height and at the same time they would turn to face the feet-end of the Coffin, putting their inner arms onto the shoulder of their opposite Bearer and simultaneously lowering the Coffin onto their shoulders. They were then ordered to turn a given number of degrees in a given direction so that on completion of the turn, the Coffin, which always travels feet first (secular), was pointing towards the right direction. The next stage was a little more difficult because it involved the strange marching I mentioned earlier, namely, making sure that the Coffin did not sway. We soon mastered this march and then concentrated on avoiding the embarrassment of me unknowingly racing ahead of the Coffin and losing control because my orders would not be heard; or, and of equal importance, going too slow and getting a bang at the back of my head. Chief Radio Supervisor Timmington (Tim) assumed the responsibility of telling me to slow down or to speed up from a basic step governed by an imaginary built in metronome of tick-tock, which I uttered to myself throughout training and on the big day itself.

The afternoon was broken up by the NAAFI tea lorry arriving which was to come morning and afternoon on Friday and Saturday. It coped well with all the men's drink and sandwich requirements, although to avoid bottlenecks the officers and senior rates had their own tea-boat in a room off the Drill Shed. Men were released to attend the promised barber now incumbent in Eastney, and also to go to the two large Naval clothing vans which were busy selling article's of new uniform for cash or on the slate (known in the Navy as the ledger).

In addition to not knowing the true weight of the coffin, we were also to experience order and counter order from nebulous sources of information. Two such events were to affect our involvement in the purchase of kit. We were told that Westminster Abbey would be carpeted from the Great West Door to the Lantern as it is on all Royal occasions. This would create problems when marching because the step cannot be heard and the rhythm can easily be lost. It would be difficult to 'glide' along on a carpet with rubber soled shoes. Therefore, it was decided that all the London Bearers would wear the same style of shoe with leather soles and heels. In 1979 only officers shoes met this criterion (ratings shoes being totally unsuitable for Ceremonial anyway) but they were approximately seventeen pounds Sterling a pair compared with approximately four pounds for ratings shoes. Reluctantly, I ordered all the men to purchase officers style shoes with a promise that when I returned to normal duty, I would do my best to get the difference of thirteen pounds reimbursed. Several weeks later, these men each received the full seventeen pounds back at the suggestion of the Captain of HMS Mercury, Captain S D S Bailey Royal Navy. As well as new shoes I also bought a new white plastic cap cover and a new cap badge. Later, on Friday, we heard that there would be no carpet in Westminster Abbey after all, but worst still, the sailors of the Bearer Party would have to wear boots with white webbing and not shoes. It looked as though the sailors would now have to buy a pair of boots in addition to shoes, but after a rather heated telephone call between myself and a Chief Petty Officer in HMS Nelson followed by an amicable person to person discussion with a fellow W.O. , it was agreed that my men would only sign for the boots on loan until after the completion of the funeral. Later on, I learnt that these boots had been written off in the same manner as the sailors suits issued to senior rates, had been. The navy has many books of reference (BR's) covering every duty, function, piece of equipment, whatever, and the BR relevant to ceremonial drill was BR 1834. In May 1972, the 1949 edition was withdrawn and replaced by an updated book. At the time of the funeral, two changes had been incorporated, the last, change 2 being issued by directive P1428/78. For some reason best known to the Director of Naval Manpower and Training, chapter 7 'funerals' still reflected the pre introduction of the Fleet Chief Petty Officer in 1970 (later, post 1983, known as Warrant Officers) even though other chapters mentioned them. It seems petty now, but such an omission caused all kinds of misunderstandings from footwear to armbands when, as written, a CPO had boots and no mourning armband whereas his replacement, the FCPO had shoes and an armband.

Shortly before tea break on that Thursday afternoon, I met Lieutenant Bob Doyle Royal Navy for the first time. He was the Officer-in-Charge London Bearer Party, and as military tradition has it, he was to march at the head-end of the Coffin (i.e., following the Coffin) leaving me at the feet-end of the Coffin to give all the orders. He looked after us very well on the administration side and he fully committed himself to being a team member. At the time of the funeral he was the Training Officer at the RN Regulating School (the Navy's Police Academy) in HMS Excellent.

Gradually we started to put things together and we finished the day with a weighted Coffin much straining of arm muscles and tired feet.

I arrived home and with my wife watched television which showed the arrival at Eastleigh Airport of Lord Mountbatten's Coffin, and those of his family who perished with him. The Coffins were carried by the Royal Air Force, put into three Hearses and then taken to Broadlands, Lord Mountbatten's home at Romsey.

Friday the 31st August started off back at Whale Island (HMS Excellent) where we were given special permission to enter the large marquee which was being prepared to house the Royal Naval Engineering Exhibition. We went there because the whole area had been carpeted with large carpet tiles, and it was considered that this would give us a feel for a carpeted Westminster Abbey. In the event it was a waste of time because the carpet texture was nothing like a quality pile carpet. Also, as I have previously mentioned, the carpet in the Abbey was a non starter, but we did not know that until later in the day.

At 0930 we went back to Eastney where we continued to practice each separate part of our duty, and when happy we put the event together bit by bit. Tim and I were growing ever more confident that with his guidance I could stay close enough to the Coffin to look as though I belonged to the Bearer Party. Using the trestles which had come with the Coffin, we picked the Coffin up and placed it down again and again lifting approximately a quarter of a ton each time. Our Instructor was Chief Petty Officer Biff Elliott who had joined the Navy with my recruitment at HMS Ganges on the 13th October 1953. He was a character with a coarse but amusing verbal patter and a man who combined humour with diligence. He applied steady pressure on our training and monitored our progress.

At 1100 after our tea break, a Hearse from the firm of Royal undertakers, Kenyon's, arrived so that we could practice taking the Coffin out of the Hearse ready for the following Tuesday evening. The driver told us that this was the actual Hearse which would be used and that he would be the driver on the day. We made a flippant comment that Lord Louis deserved a V for Victor registered vehicle and not an S for Sierra registration. The driver answered by reminding us that Royal deaths were thankfully so infrequent that it was not cost effective to have a new vehicle each time. After twenty minutes and three lifts, we were happy with what we had to do and the Hearse left the Drill Shed. Before we stopped for lunch, Bob Doyle arrived to tell us of the ever changing plan. Originally, we the Bearers, were to do our Coffin movements at the respective points of departure, and then travel to the next arrival point by a Police escorted car. Now we were to stay with the Gun Carriage throughout and march through the streets of London. We were absolutely delighted of course, but true to form in the early days, nobody would say exactly where in the Procession we would be.

§ This letter to the Editor of the Times of 1936 is of great interest and both amplifies and adds to the story on the left. Note in particular his last paragraph!

"Sir,

In your issue of January 25 (1936) you refer to the historic gun-carriage to be used tomorrow. It is stated: At Queen Victoria's funeral there was an unfortunate contretemps in connection with the horses which were to have been used to draw the coffin up the hill at Windsor, and the blue-jackets (naval ratings) manned the drag ropes in the emergency.

It would, perhaps, be more accurate to say that the contretemps was in connection with the so termed gun-carriage than "with the horses" or their handling by the Royal Horse Artillery.

February 2, 1901, was a bitterly cold day with some snow, and the gun-carriage, under the charge of S Battery, R.H.A., (Royal Horse Artillery) and under the independent command of Lieutenant M. L. Goldie, had been kept waiting at Windsor Station, together with naval and military detachments, etc., for a considerable period. I had posted N/R.H.A. which battery I commanded, in the Long Walk ready to fire a salute of 81 guns, commencing when the cortege left Windsor Station for St. George's Chapel, at about 3 p.m. I placed Lieutenant P. W. Game (now Chief Commissioner of Metropolitan Police) in command, and proceeded to the station to ensure that signalling arrangements were perfect. When the Royal coffin, weighing about 9cwt., had been placed on the carriage, drums began muffled rolls, which reverberated under the station roof, and the cortege started.

Actually, when the horses took the weight, the eyelet hole on the splinter bar, to which the off-wheel trace was hooked, broke. The point of the trace struck the wheeler with some violence inside the hock, and naturally the horse plunged. A very short time would have been required to improvise an attachment to the gun-carriage.

However, when the wheelers were unhooked the naval detachment promptly and gallantly seized drag ropes and started off with the load. The "gun-carriage" had been specially provided from Woolwich and was fitted with rubber tyres and other gadgets. This was due to Queen Victoria's instructions after seeing a veritable gun-carriage in use at the Duke of Albany's funeral, as also was the prohibition of the use of black horses.

On February 4, in compliance with the command of King Edward, I conveyed the royal coffin, on another carriage, from Windsor to the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore by means of the same detachment of men and horses. I may add that a few days later King Edward told me that no blame for the contretemps attached to the Royal Horse Artillery by reason of the faulty material that had been supplied to them.

I have the honour to be, Sir, your obedient servant,Cecil B. LevitaJanuary 27th 1936"

According to the Times newspaper of 4th September 1979 this event was to set the precedent for the Royal Navy conveying the remains of the deceased monarch (and other VIP's granted high-status funerals) throughout the London and Windsor funeral ceremonies - "When Queen Victoria was buried on a bitter February day in 1901, the coffin was taken off the train at Windsor and placed on the gun carriage. The six Royal Horse Artillery horses who were to draw it to St George's Chapel had become restless in the cold, reared and broke their traces, almost sending the coffin toppling to the ground. According to Richard Hough, biographer of Lord Mountbatten's father, Prince Louis, there was 'utter panedmonium.' Lt (later Adml Sir Percy Noble saw Prince Louis go up to King Edward, whisper something in his ear and receive a nod of assent. Prince Louis went over to Lt Noble and said; ;Ground arms and stand by to drag the gun carriage.' Senior Army officers were outraged that sailors should take over where they had failed, but the King intervened , saying; 'We shall never get on if there are two people giving contradictory orders.' The Navy, using the remains of the traces and a length of railway communication cord, began their ;stately, orderly march.'

Cecil B Levita retired prematurely from the army as a lieutenant colonel in the RHA. He was knighted for his services to the Royal Family receiving a KCVO (knight of the Royal Victorian Order). He became a very able administrator in civil life and finished his career as the Leader of the London County Council having his office in the massive building at the southern end of Westminster Bridge now part hotel and uses other than government or local government business. He died on the 10th October 1953, the very day on which I left home as a 15 year old to join the Royal Navy! His other post nominals in addition to the KCVO were CB and DL, respectively Companion of the Order of the Bath, and Deputy Lieutenant (for Middlesex), a civic role assisting the Lord Lieutenant of the county to represent the Queen in that county.

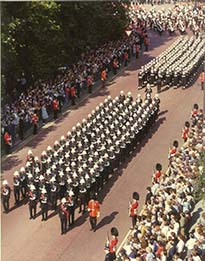

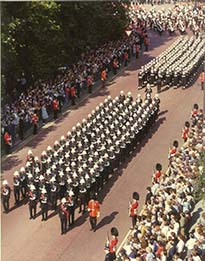

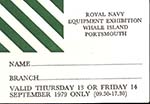

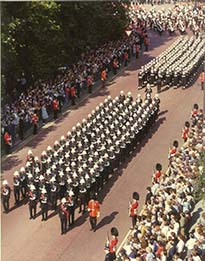

After lunch we temporarily gave up our isolated training in the Drill Shed and joined the Gun Carriages Crew on the Parade Ground. In that one and half days of training the Guns Crew had already grown into a team albeit lacking polish, but nevertheless the sense of belonging had been cemented. We were new boys, strangers in their camp and an additional burden they could well do without. We were ushered to fall-in at the rear of the Spare Numbers who were fell-in behind the Gun Carriages Rear Drag Rope Numbers. I was at the front, Bob at the rear and the Bearers in file. The Procession was formed up with the Marching Escort in front, the Massed Bands of the Royal Marines, the Gun Carriage and Crew, Spares and us, followed by the forty-odd Wrens who had just left training in HMS Dauntless, and bringing up the rear (though they would not march on the day) the Abbey Liners. The Wrens trained for the first couple of days only in Eastney, then disappeared to Guildford for joint training with the WRAC and WRAF contingents. We marched around the Eastney Barracks perimeter road and used the two gates each side of the main accommodation/Drill Shed block to simulate the Arches of Horse Guards Parade in London. Those first few perimeter marches were not good and we continuously had to change step because the Front Drag Rope Number's of the Guns Crew lost step with the Band. I am not sure why but the Band kept changing the beat, and discussions took place between the RM Bandmaster and the RN Ceremonial Staff. At last we went round looking like a military body of men and it was plain from the Instructors faces that they were happy and more relaxed. A decision was made that at 1900 that evening we would all march on Southsea front from Eastney to Southsea Pier and back, to get some idea of what we would have to do in London. The march was an utter shambles with the Band altering its beat and the leading Group regularly initiating a change of step sequence. The promenade was packed and many people witnessed our less than professional first public rehearsal which, after a short stop at the pier, was completed in darkness.

I left for home as soon as the Procession was dismissed happy with the progress we had made as the Coffin Bearer Party, but not happy with our involvement in the Gun Carriage Group.

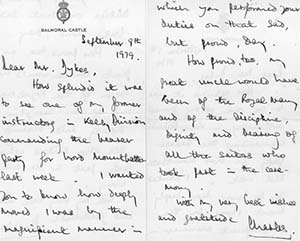

After the funeral I received so many letters praising the Bearers for their dignity and bearing. Many were passed on to me by my Commanding Officer, Captain S D S Bailey Royal Navy, and some were addressed in such a way that I wonder how they ever found me ......."English sailors in London" for example. Many were addressed to me personally. I have far too many to publish, and anyway, were I to do that the originators would not be best pleased at seeing their address published across the WWW. The following pdf file contains two letters, plus an article about our visit to Broadlands at Lord Romsey's invitation, as well as a short piece taken from the Mercury Messenger No 6 dated April 1980 (the Messenger was the Padres monthly newspaper on St Gabriel's, HMS Mercury's Nissan-hut Church. The Padre at the time was the Rev Tony Upton.

Letters and Mercury Messenger

In the article about Lord Romsey, who incidentally will become The Earl Mountbatten of Burma at the death of his mother Patricia, The Countess Mountbatten of Burma, the newspaper reporter wrongly mentions Pall Bearers. It is a common mistake made by many, and to set the record straight I thought it useful if I were to define the difference between Pall and Coffin Bearers. The Coffin Bearer is self evident and needs no further explanation, except to say that in military Ceremonial there are eight of them instead of the usual six used for domestic funerals. I have researched the reason for this but the outcome is vague leaving just two plausible answers. The first is pure and simple emotion: the need to touch and be involved in the last journey of a leader, a hero, a loved one, a martyr, and we see this sad event time after time on our television screens particularly from the Middle East where the dignity of death is lost in a mad scramble to be near the Coffin. When the Ayatollah Khomeini was buried in Iran his Coffin was nearly torn to shreds by the emotional crowd of men.

The second plausible explanation is that Ceremonial Coffins were made of solid wood, usually oak and often lined with lead, destined to lay in a vault or mausoleum rather than to be buried or cremated. Today's Coffins are rightly made from chipboard or even cardboard and are therefore less heavy.

Here I have added the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) definition of pall, and you will see that it is number 4 of a long list of definitions: -

OED Definition of pall

A pall therefore, is a piece of cloth or material held high above a Coffin by using a number of poles (six in this case- one on each corner and one either side) held by six eminent people who were known as Pall Bearers. They of course walked on the outside of the Coffin Bearers. This was common practice at Royal funerals and was used right up to the mid 19th century. In Olivia Bland's book, The Royal Way of Death, there is a rather strange picture of the Coffin of Prince Albert, The Prince Consort entering St George's Chapel at Windsor. The picture shows that the Coffin Bearers are underneath a stiffened Pall which is resting on top of the Coffin, the sides of the Pall protruding outwards for some distance at a 45 degrees angle. There are no Pall Bearers!

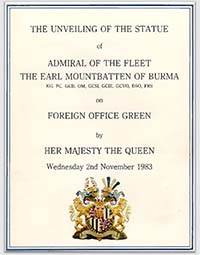

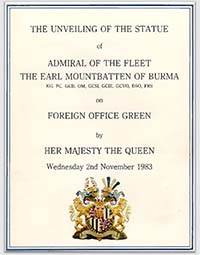

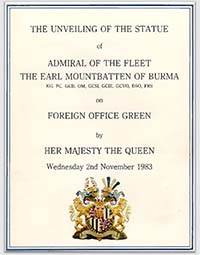

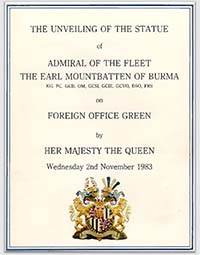

At Lord Mountbatten's funeral, the Pall Bearers were:-

Rear Admiral Chit Hlaing

General de Boissieu

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir William Dickson

Lieutenant General John Richards

Admiral R L Pereira

Admiral Hayward

General Sir Robert Ford

Admiral of The Fleet Sir Edward Ashmore.

On Saturday I left home early at 0650 and arrived at Eastney at 0730. The weather continued to be warm and sunny which made the early week-end start easier to bear. We continued with Coffin movement training until 0900, again marching up and down the Drill Shed. Shortly after 0900 the Bearer Party went by private cars to Portsmouth Town Railway Station, where a goods entrance gate was opened to allow us to park in the railway yard. To the left of our parking area was an old platform with an old goods wagon alongside, its double doors open, and to which was attached a wooden ramp. The Romsey Group, who were just completing their training using the railway carriage, left for Eastney leaving their practice Coffin for us to use. Based on their experience, we practiced a routine whereby when the leading two Bearers came to the bottom of the ramp, I halted the Bearers and turned them inwards, lowered the coffin to chest height and then side stepped up the ramp, me following on into the carriage. Once onboard the carriage, we turned right and put the Coffin onto trestles. We repeated this manoeuvre several times under the watchful eye of Fleet Chief Petty Officer Henry Cooper who was to travel with the Coffin from Waterloo to Romsey Station on the day of the funeral. His job on the day would be to take all the Ceremonial trappings off the top of the Coffin and replace them with a single family wreath, because as soon as the train left Waterloo it became a private funeral. We had mastered yet another routine with its corresponding new set of orders, and the pressure was beginning to build up. After approximately forty-five minutes in the Station we left and went back to Eastney just in time for NAAFI tea. During the tea break, Bob Doyle, Biff Elliott and I discussed the forthcoming Procession rehearsal which was to take place one hour before lunch, and which would involve us integrating into our new position in the Ceremony.

At 1030 we took our places actually alongside the Gun Carriage, each column of Bearers with Bob and I in the rear, placed either side of the great wheels, each standing approximately five foot ten inches tall. Each column of Bearers consisted of six persons who were the four Bearers, the officer or warrant officer, and a Cap Bearer. We were to maintain this position throughout the remaining training period and on the day of the funeral. The march route was now familiar although we felt a little anxious and self conscious in our new position, but after the Friday evening Southsea affair, we could surely only get better regardless of our position. The order came to step off at the slow march and the motionless three ton Gun and Limber started to move forward, their solid rubber tyres digging in and assisting traction. From my position on the outside of the Gun Carriage I had a good view of a large section of the Forward Drag Rope Numbers and they were a truly creditable sight, all in step, carrying themselves with good military bearing, and each man doing his very best to make this march a success. I could not see the Rear Drag Rope Numbers, but their leader, Commander Tricky Royal Navy, was silent and therefore I assumed well pleased with his men.

The whole march was a qualified success and the many shirt-sleeved civilians present on that warm Saturday morning, must have realised, as we did, that we were nearing our goal. We were well on the way to quote Captain Bethell Royal Navy, to nothing short of excellence unquote. The London route was timed to take thirty eight minutes and the Eastney route was made to last for approximately thirty three minutes.

When we dispersed for lunch, there was an air of confidence amongst the men, and I believe that it was at that point that those who had been compulsory recalled from leave and who were therefore not exactly pleased to find themselves undergoing parade training on a Saturday afternoon, suddenly decided that there was no way they would miss the oncoming London rehearsals and the funeral itself. It had taken nearly five days to achieve this level of morale and we had three days left in which to exploit the men's willingness to do their very best.

During the lunch period the television cameras arrived in the Drill Shed and were being set up ready for recording a programme for the national network called Nationwide. Also during the lunch hour, Biff had been talking to his fellow Ceremonial Instructors about off-caps for the Bearer Party; a routine practiced on earlier days by the Gun Carriages Crew. It was something new to learn and not at all easy. Men dressed as sailors had to master a detailed movement which was to involve putting the cap on and taking it off with the chin-stay down, using just the fingers and thumb of the right hand. We, Bob and I, had also to learn, indeed devise our own routine for removing and putting our caps on, again with just one hand. Every sailor learns to carry out certain orders by numbers, counting to themselves during the execution. In the Royal Navy, - up, two, three, down - is as well known as Nelson's name. Now there was a more involved method which had to be mastered. There was no period allowed in which to tuck away an odd piece of hair which had become trapped between the cap and the ear (for example), and if one failed to return the cap to the head so that it sat properly, the discomfort plus the odd appearance of such ill fitting headgear had to be accepted. Because of the potential difficulties of the chin-stay, a rating dressed as a seaman stood more of a chance of such a thing happening than did a person wearing a peaked cap where the chin-strap was not used.

We left the Parade Ground and returned to the Drill Shed now no longer private, but buzzing with PR personnel and television crews. Biff Elliott was on good form (or bad whatever one's view) , and sensing the TV crews, he resorted to the old-fashion Drill Instructor (he was a Chief GI (Gunnery Instructor responsible for Naval Drill)) with a few crude gestures and a couple of everyday swear words added in. We were lined up in file formation consolidating that Cap Drill we had just been shown on the Parade Ground only this time the Cap Bearers were being put through their paces. The TV camera man with the sound man were infiltrating our lines busy taking close-ups of Biff giving detailed instruction. The camera man got so close that one of the Bearers felt uncomfortable with the heat produced by the camera light and he not unnaturally showed his displeasure. Biff was in his element. "Ignore these peasants and their square eye. They are wasting my bloody time and yours. If they interfere with your concentration tell them to bugger off and if they won't, kick 'em". Many consider that Biff went too far, and I believe that after the showing of the Nationwide programme (that particular part without sound), he was sent for and told that this sort of behaviour when in the public eye, was not on. I will readily admit that I felt rather embarrassed for the Editor, Director, whatever of the programme, who was a young and pretty woman trying to do her best. Biffs actions could have been her undoing, but she took the knock well, and it was treated as Biff intended it to be, with good humour.

We broke for afternoon tea and during this period we were told that we were going on another thirty three minute Processional march, and that if it was another success like the forenoons march, we would call it a day and secure at tea time. We 'turned up trumps' again and not only did it well, but we enjoyed doing it. I found the music very sad, and of course beautifully played by one of the finest military Bands in the world; it never ceased to bring goose pimples to my flesh. I left Eastney for the last time at 1600 and spent the evening with my family.

The next day, Sunday the 2nd of September, I arrived in HMS Excellent at 0730 suitably attired to travel to London and laden down with bags and coat hangers carrying naval uniforms and accessories. Payment had been arranged for all those who wanted a ten pound casual payment, and final kit arrangements were made for those who had missed previous opportunities. At 0900, the Bearers plus an additional two young ratings mustered at the Regulating School for a final Portsmouth briefing. Lieutenant Doyle chaired the informal meeting and started the session by using the chalkboard to show us how the Queen's Chapel at St James's Palace (just one of many places he had visited during the previous day) would be laid out, and how the Catafalque in Westminster Abbey worked. Biff followed Bob to show us how he saw our routine on arrival St James's Palace and at Westminster Abbey on the funeral day. It was really academic because we did not even know how we were going to get to St James's Palace or from where we would depart. Biffs talk certainly brought home to me that we had many questions still to be answered, and it became increasingly obvious that they could only be answered by those in the know in London. Finally, I was invited to run over each set piece to say what orders I would be giving on Tuesday evening at the Queen's Chapel; Wednesday from The Queen's Chapel to Westminster Abbey, and from The Abbey to Waterloo Station.

Earlier that Sunday morning I had conducted a quiz with some of the Bearers by setting the scene, then inviting each Bearer in turn to say what the next order would be, then another Bearer to tell me what the reaction to that order would be. The two additional young sailors who attended the meeting (one a Chef and the other a Seaman) had been detailed to act as Trestle Numbers inside The Queen's Chapel, onto which we would place the Coffin on Tuesday evening. Their brief was very simple, but as you will read, these two youngsters were to be the cause of much embarrassment for me. At 1145 we took lunch and at 1415 a convoy of Naval coaches transported the whole group to London. There were so many military persons involved that every available sleeping billet was utilised, which in turn meant that Groups had to be split-up to accommodate them. The Gun Carriages Crew and the Marching Escort travelled to the Guards Barracks at Pirbright (many miles from London), and the Abbey Liners with the Coffin Bearers travelled on the same coach dropping off the Liners at the Cavalry Barracks in Hounslow then continuing on to Chelsea Barracks with our Group. Our hosts were the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards, and they made us feel most welcome.

In the evening we travelled from the Barracks in a Naval Police vehicle to Westminster Abbey but it was closed so we carried out a reconnoitre of the Broad Sanctuary and gateway approach to the Abbey. It was really a pointless fact finding trip but it served its purpose in getting the Group thinking and asking questions.

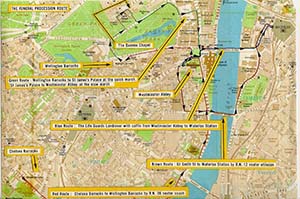

Monday the 3rd September started early for the Royal Navy Procession Contingent and the Royal Marines Band. The poor Gun Carriage Crew and Bandsmen had left 'D' Line Pirbright Barracks at 0245 and were due to arrive in Wellington Barracks Birdcage Walk at 0445. Our Group left Chelsea Barracks at 0414 after a quick do it yourself breakfast, and arrived Wellington Barracks just before the Gun Carriages Crew who had stopped at the Royal Mews Buckingham Palace, to collect the Gun; the Gun had travelled to London on the back of a Naval low loader.

It is incredible to think now, but early on this cool but pleasant and dry morning we did not know how we would get to St James's Palace; either by vehicular transport or by marching with the Gun. I don't think it was ever decided, and when the time came for everybody to take their positions, Biff told us to take up our usual positions alongside the Gun Carriage, and that on arrival at The Queen's Chapel, we would devise a routine to leave the Gun to do our own thing. When all was ready at 0530, the Garrison Sergeant Major (GSM), a very important Guards Warrant Officer called Dupont, gave the order to quick march. The Band began to play and we left Wellington Barracks through the West gate. The idea was to show us the route and the room we would have in which to manoeuvre the Gun. We crossed Birdcage Walk, marched to the East of the Queen Victoria Monument, entered The Mall and at this point the Band ceased playing as a whole, reducing its output to left foot beats on a few drums only. At the first turning left off The Mall (Stable Yard Road) the drum beats ceased and we wheeled left through the narrow ornamental iron gates, past Clarence House the home of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, right into Cleveland Row and again right into Marlborough Road. The group stopped outside The Queen's Chapel and we Bearers were fallen-out and mustered at the rear of the Rear Drag Rope Numbers. It was decided there and then, that tomorrow Tuesday for the full dress rehearsal we would march at the rear of the Gun from Wellington Barracks to The Queen's Chapel in such a position, that when the Gun Carriages Crew was brought to the halt, we would halt exactly opposite the small door leading into the Chapel. We would then take our caps off, the Cap Bearers in each column would collect them moving back to their positions on the Limber wheels with caps they had collected.

The above picture will help you identify the Limber of a Gun Carriage. The large number of dots represents sailors who pull the Gun (the Forward Drag Rope Numbers) and the small number, the Rear Drag Rope Numbers, who brake the Gun - the ropes have been left out of the picture. Thus one can see the direction of travel. The Limber is the box at the front loosely connected to the Gun, and what appears to be a TV aerial is the Limber pulling handle. You will observe that each (Gun and Limber) has two wheels. The Limber carries the shells to be fired so that when the Crew goes into action, the loose connection is disengaged, the Limber is placed some distance behind and away from the Gun and those attending it supply the Gunners with shells.

Then we were to turn left and enter The Chapel for the Coffin. It was another new routine to learn, and I could sense the concern and anxiety on the faces of the younger members of the team. Changes in routine so close to the event were undesirable, and I tried to calm my men by telling them just to listen to my orders and all would be well. I almost enjoyed assuming such a responsibility although I was aware that if I forgot the next order, catastrophe would soon follow.

We re-Grouped and on the GSM's order, stepped-off at the slow march. We marched down Marlborough Road, left onto The Mall, right into Horse Guards Road, left through Horse Guards Parade and through into Whitehall. On passing through the Arch and through the gates at the Whitehall end, we had very little room for error with the Gun and the approach was critical; the main Arch/gate was so narrow that the Coffin Bearers (and on the funeral day proper the Pall Bearers) had to march through the side Arches/gates.

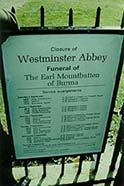

At this point of the march we had seen very few people watching the first rehearsal, but as we proceeded further down Whitehall, more and more early morning workers enroute to their place of work stopped on the pavement and almost stood in a silent and sombre manner. We continued into Parliament Street, on into St Margaret's Street and then wheeled right, past St Margaret's Church (where Lord Mountbatten was married to his wife Edwina*) and into Parliament Square. As we approached Broad Sanctuary we could see several large television vehicles parked close up to the North wall of the Abbey with several workmen playing-out cables and erecting platforms. We were to see a great deal more of these people during the next two days, but the first sight as dawn broke was enough to excite the imagination. We continued to wheel right around Parliament Square, left into George Street and on into Birdcage Walk finally to re-enter Wellington Barracks by the East gate at approximately 0650. There were many people on the streets by this time and certain roads had been closed off. We left Wellington Barracks and returned to Chelsea Barracks for a good hot breakfast.

*Edwina died in 1960 and was buried at sea from the frigate HMS Wakeful off the Isle of Wight. Her coffin was piped onboard as one might expect. However, Lord Mountbatten turned to Nehru and said that it was an honour which I have never before known to be accorded to any woman other than a reigning sovereign.

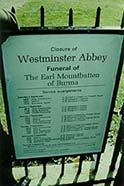

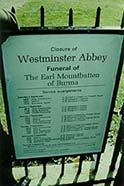

At 0900 we went to Westminster Abbey for our first rehearsal. On arrival, there was much activity by large numbers of television workmen, Department of the Environment (DOE) artisans (who had created a false front to the Abbey entrance to house a television camera without the camera giving offence), and many others. There were camera platforms everywhere - inside and outside the Abbey - and enough twenty two inch colour television screens to supply a medium sized village. The television screens were sited throughout the Abbey so that persons privileged to have a seat could watch the Procession and parts of the Service within the Abbey hidden from their view. There were two Groups practicing: the Abbey Liners made up from men of the Royal Navy, the Life Guards and the Royal Air Force Regiment, who collectively, formed a column either side of the route from the pavement iron gates to the Great West Door, the other group being ourselves. Inside the Abbey, in a corner of the North West Nave was a Coffin, much larger than that we had been used to, and with a size six breadth Union Flag. The Coffin belonged to the GSM HQ London District, and we were told that it was weighted according to the rules; just another of the nebulous statements we heard over these days. We started our training in-situ by informally walking through the Abbey to the Lantern to view the Catafalque. We had been told previously that it was a very old and rickety wooden framework, unstable and fraught with danger. Our informant was absolutely correct! The Catafalque had fixed rigid wooden slats and no rollers. It had a wooden peg at the feet-end which stopped the Coffin from being pushed too far, and the whole thing was designed to turn 360 degrees. The mechanism to lock it into position feet facing to East or feet to West, was badly worn, and the whole assembly moved several degrees to left and right from its intended lock position.

We returned to the entrance of the Abbey, picked up the Flag draped Coffin and began our first practice, marching to the left of the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, down through the Curtain, the Choir Stalls, to the Lantern and placed the Coffin upon the Catafalque for the first time. The Catafalque demonstrated all its known shortcomings, and during the placing of the Coffin (which was difficult without rollers) it swayed from side to side in an exaggerated and disturbing manner. During the march to the Lantern, Bob Doyle had been very concerned about the way the Coffin swayed from side to side, this despite the special step which we had virtually perfected in earlier training, and he considered that the irregular sizing of the back two men (head-men) was a contributory factor, and one which could only be rectified by change. Leading Radio Operator Foster was singled out for change, and being a person who demonstrably showed his emotions and inner feelings, his reluctance to change temporarily destroyed his morale and his willingness to co-operate. He was happy in the position in which he had spent five days of dedicated training, and any change now would not only involve his Coffin work, but also his position marching on the Gun. Bob was very accessible, and I discussed the morale vis-à-vis the swaying of the Coffin with him. He readily agreed that we should give the Bearer the benefit of doubt and see if the same swaying occurred on a second march. Throughout the whole training period, each member of the team was encouraged to voice constructive criticism if they considered it in the best interests of our overall performance. I cannot recall which person suggested the check, but all agreed that the head-end of the Coffin was extraordinarily heavy. A screwdriver was obtained and the lid removed; the cause of the swaying was immediately obvious. The Coffin was weighted with iron ingots most of which had left their appointed places and had ended up at the head-end, and poor Foster and his opposite Bearer had actually staggered down the aisle shouldering an enormous burden. The ingots were re-positioned and secured, the lid secured and a second more successful march to the Catafalque was completed. We did one more journey, took the Coffin back to where we had found it, folded and placed the Union Flag on top, fell-in and at the slow, I marched the Bearers out of the Great West Door into the cobbled courtyard. At the Great West Door there are three steps of uniform height (give or take an inch or two) but with different widths, and we practiced going up and down them to achieve synchrony of step before and after ascending or descending. It was a simple evolution for me but more difficult for the Bearers with a heavy Coffin, and one we did not perfect because our programme time expired.

Above, I referred to the Union Flag as being a 'size 6 breadth'. This merely indicates the physical size of the Flag ranging from a small one as flown from the jackstaff of a Submarine in harbour or at a buoy, to a huge Flag as worn on the Buckingham Palace flag pole.

The Coffin at any funeral is the centre piece to which all eyes focus. The way it is moved dictates the tone of the funeral. When that movement is closely monitored by television and in real-time shown to the world, it is doubly important that it is dignified. The three steps at Westminster Abbey are enough to momentarily pierce the shield of dignity. Knowing that, I am in awe of the Guardsmen who carried Sir Winston Churchill's Coffin up the many steps into St Paul's Cathedral and to the Guardsmen (and other soldiers) who have successfully negotiated the very steep steps leading to St George's Chapel at Windsor, particularly at the funerals of King George VI, the Duke of Windsor, and recently, Princess Margaret.

We returned to the Lantern where a retired Major, now an Abbey official, showed us to our seating area which we would use during the service on Wednesday. We completed the days training in the Abbey by slow marching to our seats, and then, on cue from the Major standing in an adjacent aisle, returning to the Catafalque.

The next part of our training was to be in stark contrast to all that had gone before, and to say the very least, dramatically exciting if not foolhardy!

On the day proper, the final act was to be on platform 11 at Waterloo Station. The Coffin, to be conveyed by a specially converted Land Rover belonging to the Life Guards, was to leave the Abbey, and travel across Westminster Bridge to Waterloo. We were to put the Coffin onto the Land Rover after the Service, and then we were to travel at full speed across Lambeth Bridge to arrive Waterloo Station before the Land Rover, to be ready to take the Coffin off and place it onto the Special Train for Romsey in Hampshire. Parked on the corner of Great Smith Street and Broad Sanctuary (out of sight of the Abbey) were two Royal Navy twelve-seater utilecons to be driven by sailors (Regulators in Navy speak, Policemen in civilian speak) from the Naval Provost Marshal London HQ's. With them were two Metropolitan Police motorcyclists who would act as escorts and out-riders. On leaving the Abbey we assumed that we had placed the Coffin onto the Land Rover, and began the slow march in the direction of Deans Yard, breaking into the quick march when opposite the yard entrance. On reaching the corner of Great Smith Street we broke off and ran (literally) to the waiting vehicles. As soon as we were all onboard (but not necessarily with the doors shut), the two motorcyclists and the two utilecons proceeded down Great Smith Street as though their drivers were possessed with the devil. The traffic was at its usual peak -chaotic - bumper to bumper at five to ten miles per hour. We proceeded at forty five miles per hour first on our side of the road then on the other side, wrong way around keep left bollards, cutting across roundabout traffic flow, forcing traffic to our right to brake and take avoiding action. There was utter chaos and the drivers who were flagged down by the skilful motorcyclists , were obviously irate and blew their horns in retaliation. We crossed Great Porter Street against the lights, on into Marsham Street, right into Horseferry Road on two wheels, then negotiated the two roundabouts either end of Lambeth Bridge with blind madness as our guide. I travelled in the front of the leading vehicle, and whilst I will give credit to our driver for his driving skill, I did travel down Lambeth Palace Road with doubt in my mind that we would arrive safely at our destination. The last half mile or so was just as hair-raising but a little safer, because as we approached the railway station, more and more Policemen started to control traffic and pedestrians. By the time we turned into the Station the British Transport Police had cordoned-off the access which led straight onto the wide roadway adjacent to platform 11. It was almost with relief that I stepped down onto the platform, but I cannot deny experiencing a boyish enjoyment at our Keystone Cops type trip.

Much of the entrance to the platform had been painted with dark red and black colours, and propped up alongside a large ubiquitous roof support pillar was a newly made wooden ramp, which had been painted with non-slip grey coloured paint on all visible projections. The Special Train was not in the Station and the track alongside the platform was empty. From our practice time in Portsmouth Station we had acquired the necessary knowledge for taking the Coffin up the ramp and onto the train, and all we required to know about this Station was where to stand to await the arrival of the Land Rover, where to stand on leaving the train before it left for Romsey, and the construction of the railway carriage Catafalque which would affect our angles and turns on entering and leaving. The other outstanding procedure was in the use of the Land Rover and its peculiarity, but that was scheduled for later in the day. The position of the Land Rover when stopped on the platform was critical to our relative starting position on the platform because we had to wheel around to get the Coffin, and then turn with the Coffin so that we were directly in line with the ramp. It would therefore be necessary for our group to determine where the Land Rover should stop, and having done so, to decide where we would stand. When all was finalised and I had computed an additional half dozen orders, we boarded our vehicles and this time we drove to Chelsea Barracks for lunch obeying every traffic sign, speed limit and convention.

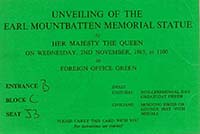

Official Order of Ceremony.